The video embedded below, along with the draft script and supporting links, can be freely…

This collapse, my art, and what I think I can see

by L.A.W., a well-traveled artist-educator living in Ohio

I recently read that Michelangelo stopped making art for two years because the Republic of Florence was under attack and he understood it to be his duty to contribute whole-heartedly to the survival of his country. I don’t flatter myself that I am like Michelangelo when it comes to skill and genius, however I do regard Petrocollapse (or Peak Oil) as great big news that gets virtually no coverage in the media. Without discussion and awareness, very little can be accomplished as we attempt to mitigate or prepare. As a visual artist, I understand I am part of “the media,” albeit a tiny one. Because of this realization, I spent quite a bit of time and money “making a statement.” (I think all artists, especially visual and performance artists, should pitch in for this one.) The statement that I made was, in essence, Petrocollapse is likely going to cause the deaths of many, many people, and because of the apparent scale of the catastrophe, everyone should be invited to contribute to “softening the crash” in every conceivable way. Oh yes, and Americans will be the hardest hit.

That statement met (and is meeting) with mixed reviews. Most commonly, people seek refuge in denial and they explain to me that technology will be harnessed and come to our rescue well before any disaster that would make World War II seem like a reprieve. Because they saw the artwork, and because I gave many of them a photocopy, I don’t try much harder to convert anyone. Still, I have come to believe that the images initiate the grief process enough to start raising awareness — a seed gets planted. The sooner people meet their denial the sooner there can be hope of that denial being overcome. (I worked as a chemical dependency counselor for four years.) That is also why I decided to put the images in the creative commons and give them away. What began as my using art to cope and process difficult realizations has become what could be a tool for raising awareness. I think art does this for me more than a graph … although I must say, graphs too can reach me. When I first saw and looked at the oil poster I went home and made a yellow Star of David with black outlines. In the middle, in Hebrew-esque lettering, I wrote “Peak Oil.” My friend Gordon Baer photographed me holding it against my suit coat where the Nazis required Jews to wear similar stars that said “Jew.” I did that because it communicates the peak oil-based Holocaust on an unimaginable scale. My awareness became oppressive and the only real coping skill for me is to make art about it. The more I learned, the more I found that the Black Death is the only event that compares at all and its influence on European culture gave us the longest running genre in the visual arts. I had to cross Danse Macabre imagery with issues of Peak Oil.

For this printmaker, the project went from photographing skeletons to arranging them in Photoshop to having the images laser cut into end-grain maple blocks and then printing them the very, very old fashioned way. I now realize I was losing valuable time relative to the larger purpose of the work. At first I envisioned making a few quaint but remarkable books but then the photocopied versions were so much faster and cheaper to generate and then once friends on the web saw the digital images, they helped me realize that a pdf file would be the swiftest and most easily shared version: Dans Macabre ad hoc Petrocollapse (large pdf).

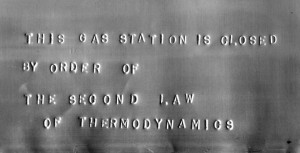

My encounter with Peak Oil turned me into something of an activist, helped un-job me and is putting stresses into my life and marriage that are best dealt with using close and caring support groups. Because such local support groups don’t exist yet, we have to build them. (Nationally and internationally, Awakening the Dreamer workshops do help with this.) That adds more stress — however we are collectively reaching a public awareness tipping point. That is another reason I created what I refer to as “the little artist’s book” or “the doomer comic book.” For the same reason, I give it away. For the same reason, it is in the creative commons. Such efforts get us closer to public awareness in an arena that non-artists rarely step into. Such visual efforts reach out easier because they can jump the gulf between intellectual and non-intellectual, businessman and student, parent and teenager. The curious little pictures should be seen some place (many places!) to make some people ask questions. But it seems most people are too busy to bother with the collapse of their civilization. They would rather not deal with unpleasantries. When I pitched my most recent proposal to a group of artists at a gallery, I was very serious and earnest and my suggestion was met with peals of laughter. Not the kind of laughter that arises from a sense of humor, but instead the laughter that comes from sudden confrontation with what one regards as absurd. Humor is very important in facing the issues related to the depletion of our primary energy source. I have formed this opinion because laughter is adaptive and can facilitate discussion. The assumption that oil supplies will last forever is so entrenched that to actually question it can demolish one’s worldview. That is not a good feeling and humor is one of the few ameliorative tools in attempting to actually engage in dialogue. A nurse, who is an active member in the Transition movement, told me, “How you make them feel is almost as important as what you tell them.” When she said that, it occurred to me that the navy never seemed too concerned about feelings when the captain orders “man your life boat stations” and the Eugene Kleiner saw, “There is a time when panic is the appropriate response,” also crossed my mind.

We generally regard the unthinkable as absurd. But just because we don’t think about something certainly does not place it into the set of “impossible.” The unthinkable happens. When it does, we often are struck with a kind of awe. Encountering awe is another purpose in art. Journalist Bill Moyers interviewed a soldier who witnessed the huge counter-attack of the German army at the start of what would become “the Battle of the Bulge.” The soldier described it as “sublime.” I lived with a painter who was the first to tell me that not all art is beautiful. Some of the most powerful art is sublime. I was pleasantly surprised to see this confirmed by a curator giving my Danse Macabre work an award when I regard the images as “horror laced with gallows humor.” (She saw the large four-feet-high, carved versions.)

For those who wish to see the images as they were first posted in their blog context, they are posted here. Please share them.

Our preoccupations with our occupations often help us forget awe. In the Vedas it says, “When the people lose their sense of awe, there comes a visitation.” Our society lost its sense of awe (I believe) once consumerism got a good head of steam. Our value of human life is threatened by its over-abundance. Now we are torn between participating in a paradigm that cannot continue (growth forever) and going into forgotten territory that will feel uncharted because support is gone. (For example, harvesting wheat used to be a huge community effort. With petro-energy, large combines do what neighbors used to. Another example, if I do not get an earn-money job, I risk losing my home.) Soon we likely will be re-pioneering an urban and suburban wilderness in an environment of diminishing energy. (The Transition movement, started by Rob Hopkins, et al. is helping accomplish this vital work.) Unfortunately, the fuel most people will fall back on will affect an even steeper ecocide. We seem to be the fleas on a dog called Earth. We are invited by circumstances to come together in conscious conservation of limited resources. A learned friend recently pointed out that some who cannot or will not hear or understand the invitation are merely selected against. What the “preppers” are doing is prepping the follow-on gene pool.

The lessons our society needs most were learned long ago. They were embedded in the stories that we told that incorporated the value of the soil and our connection to the earth. The mythologies that tend to separate us from the earth are not as useful to us, now that we see they have led us into destroying our habitat. The messages we send to ourselves are about to change radically. The survivors of this die-off will have values that are very, very different from ours. There is a sacredness of the earth and connection to it that we have missed. It is soon to become very clear. Physicist Robert Hirsch claims that within two to five years it will be clear to everyone that we are in a very serious energy “mess.”

From the ancient stories, we know, intuitively, any who survive past the steepest part of the energy descent curve — those who understand what needs to be done and are willing to risk everything to help others to do the next right thing — they will be the heroes about whom our great-grandchildren sing. The one who goes past the known world (physically or conceptually) and returns to use the experience to help society: that’s what a hero is. More important than a mere “hero-story” is the actual function of such stories. We wrongly believe that myths are just old religions from other places or peoples. We have told our conceited selves that myths are things we do not need. We do need them and very badly. The purpose of a myth is to guide the individual and the society in living correctly in relation to the material world and the cosmos. Myths work like pictures and often on the same level. If I know the myth, I understand the meaning. The weakness of our civilization has been a lack of reverence for the awesome power of the mysteries in nature. We dismissed the “nature religions” as primitive. Impressed with using our science and technology, we flatter ourselves that we have conquered nature. Unfortunately, as C. P. Snow points out, technology offers us gifts with one hand and stabs us in the back with the other. Peak Oil and climate chaos are stabbing us in the back. Native Americans looked with suspicion on our culture’s fondness for innovation. Why risk the balance that affords life? While I don’t regard myself as a Luddite, or anti-technology, there is something to be said for long-term stability. Icarus was not deaf to warnings. He became intoxicated with the amazing power he briefly harnessed. We have briefly harnessed oil power. My grandfather harnessed horses to drive into town. Before I die, I may do the same.

I’m an old destroyer sailor and I believe there should be a plan for every conceivable scenario that we are likely to encounter. I instinctively started down the path of energy decline by trying to talk to commissioners and city planners to raise their awareness (“use your chain of command”). I was very naive. I still give talks where I teach and I have spoken to a group of Rotarians, but such approaches — trying to convert unbelievers — is very slow going, isolating, and a drain on energies better spent elsewhere. I still write articles and post to blogs, but there is a real need for activism of the embarrassing sort. The kind where someone cracks someone else’s weltanschauung out of a sense of community while in public. That’s a rare opportunity and a rare person who seizes such an opportunity. Performance artists are useful in that role. Puppeteers are also very useful in that role. I have taken to occasionally asking a stranger as we both get gas at a gas station, “Do you ever wonder how long we’ll be able to do this?” A surly person might think, ‘mind your own business,’ and that’s exactly what I think I’m doing. An uninformed community is a hard-hit community. John Seymour told Davie Philip that instead of self sufficiency, he should have written a book about co-sufficiency.

I’ve started making a list of “things that will be different” in Energy Descent and all the ways they will be different. I believe that the technologies and skills used to help get us up the per-capita energy consumption curve (e.g., Dr. Richard Duncan’s Olduvai Theory of Industrial Civilization) will apply to getting down the curve. The first up will be the last up, in a general sense (e.g. biplanes will fly later and longer in history than Boeing 787s). Generally speaking, “everything old will be new again.” My list is becoming my next art project, so that awareness can still be raised. Experience of truth, or even just truisms, is an aesthetic experience.

Since we have such a late start, my wife and I have ten acres and we have been learning everything we can about growing, processing, and storing food. I raised an acre of wheat and rye and did everything by hand to end up with bread — including building an earth oven. We keep enough stored food to last a year, including barter and charity. We are building resilience and community and trying to participate in Transition efforts.

I used to regret having changed trades or jobs or careers so often. I sometimes thought I was too much the pinball, bouncing from one interest to another, from one job to another … I sometimes believed I was too much the generalist and not enough the specialist for having gone from science to languages to art. Any more, I appreciate that I have been adapting and preparing. I have adapted fairly well. Others have not. Those of us who have adapted reasonably well may want to help those who have not. In the past when “haves” chose not to help the “have-nots” for long enough, bad things happened. That’s why one of the aphorisms for my exhibition will be a paraphrase of the rules of the board game Monopoly. “When one person owns everything, the game is over.” Another is “Nature draws more than ten oxen.” That’s very much like another I will use: “Nature bats last.”